Welcome to The Blazedmade Interview. Here we bring you exclusive, intimate and engaging conversations with those who live at the intersection of hip-hop, fashion and culture.

We’re thrilled to kick things off with Ithaka Darin Pappas, who in 1988, was annointed N.W.A's official photographer by the groups label/distributor Priority Records.

Blazedmade founder Daniel Cutler spoke with Ithaka at his home in L.A. where the photographer-artist-surfer detailed the unknown story behind his iconic N.W.A "Miracle Mile” shot, an increasingly important image in the history of hip-hop.

The two also discussed the day skateboarding went gangsta rap, and how, unbelievably, most of Ithaka's N.W.A photos have never actually been seen.

BM: Where are you from and where did you grow up?

DP: I’m from southern California, lived between and LA and Orange Country most of my life.

BM: When did you start getting in to photography?

DP: I’ve always been in to it. My dad was a devout hobbyist, I’ve been shooting photos since I was five years old. I sold my first picture when I was 17 years old.

BM: Who for?

DP: Independent - a skateboard brand. In 1984 I think.

BM: Sure I know Independent. Did you skate?

DP: I’m a surfer. I was really just photographing skateboarders. I skate but I was much more behind the camera in that activity, whereas in surfing I was not behind the camera at all.

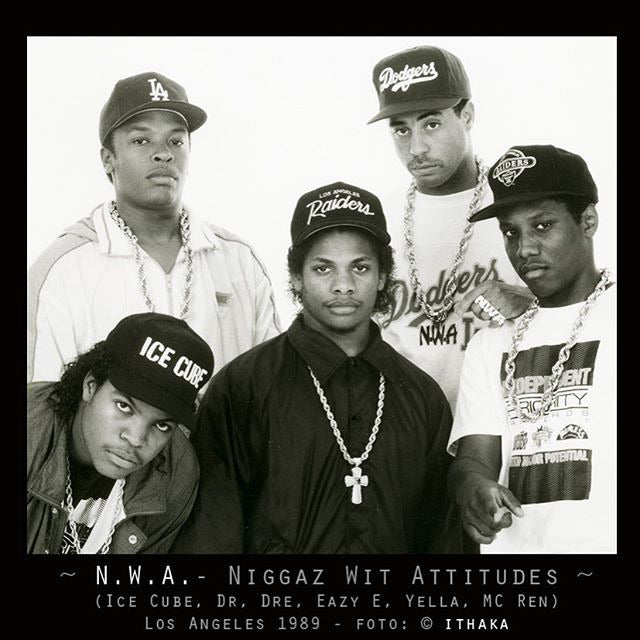

N.W.A Miracle Mile photographed by Ithaka Darin Pappas, Los Angeles, 1988.

BM: What is this photo known as? When and where was it taken?

DP: This photo is known as The Miracle Mile. It was my first time photographing N.W.A and my first time shooting for Priority Records. It was intended to be the shoot for the cover of Eazy-E’s single “We Want Eazy". We were also trying to get publicity photos of N.W.A, as a group, which I didn’t get a whole lot of that day. We were also doing some publicity photos for Big Lady and she came by the shoot also.

BM: As in Big Lady K?

DP: Yeah. She’s a rapper, half-Guatemalan, half-black from Riverside. She was fifteen at the time. An amazing talent.

There was no directing anybody. They come self-contained. You can pare down the shoot to a point, but everybody's individual personality is so strong, they're not very moldable.

BM: How did you land the gig? How did you connect with Priority?

DP: It was completely by coincidence. I was already shooting stuff in the entertainment world, mostly young, teeny bopper stuff. I was looking for something edgier. One day I was skateboarding down my street, in an area known as the Miracle Mile, and a neighbor of mine pulls up in the driveway next to mine with a ton of groceries, and I asked if she needed some help. It turned out to be one of the Marketing Directors at Priority. She invited me to go show my book to the Art Director over there. So the next week I went in to show my book to the director, Elaine Friedman, and it worked out.

BM: That’s so random.

DP: Yeah - and I was totally an N.W.A fan. Gangsta Gangsta was blowing up K-Day which was the main radio station at the time. I mean, I was really listening to this stuff a lot. Then suddenly these guys (N.W.A) were in my living room a couple weeks later. It was pretty cool.

BM: What year was this?

DP: This was November of 1988, I think it was November 11th. It was around the near simultaneous release of Straight Outta Comptonand Eazy’s first album (Eazy-Duz-It), they came out almost the same time. It was like a grand slam, it was pretty crazy, they were everywhere!

Eazy-E, Big Lady K and N.W.A "Miracle Mile" Contact Sheet, courtesy of Ithaka Darin Pappas.

BM: Yeah, they were released a month apart I believe.

DP: Yeah, I just remember Eazy and everybody rolling up to my place, which was in a really quiet semi-elderly Jewish neighborhood. They roll up in a GMC Safari, and they were just blasting the music! The neighbors were like “what’s going on?” It was great because I couldn’t stand my landlord at the time.

BM: Ha! No one’s going to mess with you in that scenario.

BM: Where on the N.W.A timeline did the Miracle Mile shoot take place? Were they mostly an L.A. thing at this point? Or was it bigger than that?

DP: Well, I was only in L.A. so I don’t know. But in L.A. they were absolute underground legend status already. I don’t know how much mainstream people really knew about them, but in my world they were already household names after just six or seven months. [Ithaka chooses his words carefully] It was just such a raw…I think the thing that set this project apart…people that live in the suburbs were really aware of…I heard Cube say like a hundred times that N.W.A were street reporters, and nothing could be more accurate. At that time, all the violence happening was really behind the curtain. N.W.A brought us this slice of another reality, their reality, and it was really eye opening for a lot of people, myself included.

BM: Yeah, me too. So explain how the shoot went down. Did they hand over the reigns to you as the director? Did they take your direction?

DP: There was no directing anybody. They come self-contained. You can pare down the shoot to a point, but everybody’s individual personality is so strong, they’re not very moldable. It was their time, it was their world. I was more a fly on the wall, trying to capture what they were all about. I was trying to record who they were.

BM: So this iconic image of gangsta rap's founding fathers was shot in your apartment?

DP: Yeah, at 65** 1/2 Orange Street, L.A., Wilshire and San Vincente. Near the Museum Row area. They just came over. One thing I had noticed, even at this early point, was that there weren’t a lot of clean shots of them together. They were either riding, in the street, on the move, in sunglasses. It was hard to see what they looked like. For this shoot, I was just trying to show their faces. Like I was shooting for a fashion magazine. It was shot in my apartment with a couple of studio strobe heads. I had rented a Hasselblad camera, a high end camera. These were smaller budget shoots, the entire budget for that day was maybe five hundred dollars and that was to include film and everything. I spent way more than that because I wanted to do a good job. These were people whose music I loved and people who I admired. I didn’t know if I was ever going to shoot them again. I wanted to do a kick-ass job first time around.

BM: So you sensed that this could be a game changer for your career?

DP: Yeah, I mean I had no idea they were going to blow up to become, you know, millennial figures. I had no idea it was going to go that large, but I knew this was something special.

BM: So what where they like? Describe their individual vibes.

DP: They were definitely tough guys, but also very funny, especially amongst themselves. Super funny cats.

BM: Yeah, I hung out with Eazy a couple times and he was fucking funny! I don’t think people realize how huge a role humour played in his personality.

DP: Yeah, Eazy had an incredible sense of humour. He had absolute star quality. And he was also extremely easy to photograph. Out of the entire group he was the easiest. I mean he was so stylized, and he was just easy to work with. I found Dre to be pretty shy, photographically. Eazy was a clown, a funny guy. Ren was really tough. Yella was really nice. Cube was serious and determined, his intelligence absolutely permeated, really obvious, I could tell how high the guys IQ was after just a three minute conversation. Then I think we ended getting a bunch of nachos and drank old English. It got loud, it was fun.

BM: What was your relationship like with the guys at the start?

DP: (Laughing) No one really remembered my name.They just called me “the camera man”.

BM: I guess it’s obvious why.

DP: Well, we were shooting and the music was on, it was really loud. I was kind of standing on a stool, dancing to the music a bit, and Ren kinda pointed at me and smiled and said “check out the cameraman”. From then on i was “the cameraman”. I don’t think anybody called me anything but that from then on.

BM: How many sessions did you shoot with N.W.A? Over what period of time?

DP: Well beginning in ’88 and ’89’, ’90...and I shot Ice Cube I think in ’91. So I would say three years. Photographing them every two months. I would say it was a about three years. I think eighteen to twenty shoots total.

BM: Wow. So you had this access to them from the very start, through their break-up, and afterwards?

DP: Yeah and that was interesting too, because you know, arriving that first day, there was probably some live shows, nobody was really getting paid yet. Then two months later, people are driving nice cars. It was interesting to see it from a distance. I didn’t consider myself a friend, we didn’t really hang out, other than the Malibu “Wild and Wet party” but I would see them periodically and they were really getting famous so i would see, not really a difference in behaviour, but the accessories got a lot nicer!

BM: No doubt! So over the period that you shot them they were going through a lot of internal conflict. Were they still together the last time you shot them?

DP: No, the last time I worked with N.W.A as a group Cube had already split. I worked with Cube a few times on his own projects, for video shoots and UK music magazines. That was as far as I got, I didn’t see Dre leave the group. I had moved back to Portugal by that time.

BM: Did you shoot Dre solo as well?

DP: Not really. I mean I shot him by himself as a member of N.W.A. I would always pull people aside for little shoots. I did that with Dre. It was very improvisational. The one record cover that I shot, the only time we ever really had a layout, was for the We Want Eazy 12” cover. Everything else was “go out with the guys, get what you get". One of those images, a bleacher shot in McArthur Park, ended up as the cover for the Express Yourself (single) and Straight Outta Compton maxi-single cover. Mostly I would just try to pull people aside and get a few shots. In a way it kind of dictated my whole style of photography from then on, because I was so limited on time with everybody that it made me work faster and try to come up with things on the fly that professionally looked like studio set-ups but with natural light and trying to keep a wall, you know, so I’m kind of thankful for that experience. It was like guerrilla shooting.

BM: What equipment were you shooting on over those eighteen shoots? Was it one main camera?

DP: I shot the Miracle Mile image on medium format Hasselblad. Most of the other shoots were on Nikon 250 FE, you know just a standard camera. It was photojournalism. I was just trying to get portraits. But that first shoot (Miracle Mile) I shot that on medium format ultra high quality. It was a camera I used for my actor shoots, I was already familiar using it in the studio so that’s what I brought to that shoot. I rented all the gear and we shot it in my living room.

BM: You also shot a series of photos with Eazy-E in Venice, skateboarding, which have become quite iconic. Can you tell me about those?

BM: You also shot a series of photos with Eazy-E in Venice, skateboarding, which have become quite iconic. Can you tell me about those?

IDP: Sure, N.W.A were doing a feature on Yo MTV Raps with Fab Five Freddy. He was out from New York and they were working around L.A over a couple different weeks. That particular day, I think it was February 24th 1989, Fab Five Freddy was interviewing the guys in Venice, out in the public, which was super interesting because they were ultra famous by that time. They really caused a scene. Eazy wore a bullet proof vest that day. I don’t think it was a publicity stunt I think he used it for legitimate reasons.

BM: He wore the vest on the outside didn’t he?

IDP: Yeah he wore it on the outside. People were going crazy, signing autographs. Fab Five would interview everybody in the group separately. I was there to document everything, so when guys start wondering off from the group, I wasn’t sure what to do, but obviously I had to photograph the interview with Fab Five and Eazy, two legends of hip-hop. I see Eazy kind of walk over and start talking with all these skateboarders. At that time skateboarding and hip-hop didn’t have much of a relationship, so I was like, what’s going on over there? I followed him over there and then he gets on this guys board and starts skating. He had obviously spent a lot of time on a skateboard he knew what he was doing. He skated goofy, right foot forward. It was quite a surprise.

Eazy-E and Fans, Venice, Contact Sheet by @_Ithaka, 1989.

BM: Did you realize this could be a cross-over moment between two cultures?

IDP: At the time, I didn’t really understand the significance of it. Now that I look back on it, I think Eazy-E publicly associating with skateboarding at that moment, he kind of introduced it as an urban friendly sport to more than just white suburban punks. Like suddenly it was okay for anyone to be a skateboarder. It was a pretty cool moment and it was a case of just being there and I shot some good quality photos. I think they’re the only photos of Eazy skateboarding that i’ve seen. That’s part of the photography thing, you know just being there.

BM: It’s hard to imagine hip-hop culture and skateboarding culture being so seperate. Today it’s hard to find a skate video without hip-hop in it.

IDP: In the 80’s skateboarding was mosty linked to punk rock. But hip-hop is, you know, a different kind of punk rock. It’s rebel music. And people tuned in to that. Thrasher Magazine ran a bunch of my photos of Eazy skating from that day. I’m not even sure how they got hold of them. They used them for an ad and a t-shirt, and that moment became embedded in late 80’s culture.

BM: Did Thrasher pay you to use the images?

ITH: No they didn’t! They actually credited and paid someone else but that’s a subject for another day!

BM: Speaking of licensing, can you tell me about how licensing your N.W.A images works? For example, with the Miracle Mile shot, the image is definitely out there on-on-line so people have access to it. I’ve seen it on t-shirts for sale but to be honest it’s usually cheap looking. It’s such a an iconic image of N.W.A yet I don’t think I‘ve seen a legit brand use it.

ITH: You’re right. In fact, you guys (Blazedmade) are the first to license it for clothing. I think that of the main N.W.A photographs it has been the least merchandised. I’m so happy to have it see some light now.

N.W.A Express Yourself Unisex Tee (above) . . . N.W.A World’s Most Dangerous Unisex Tee (below) . . . Available exclusively on Blazedmade.com

BM: Over the course of a group’s career, there are thousands of photos taken but usually it’s just a handful that come to define the group visually. You have arguably “the one” image that defines N.W.A. How does that feel?

IDP: It’s a really special feeling. It’s a tough thing to top in a career. That’s what I feel like, the Miracle Mile image is “THE” shot of N.W.A. They were inducted in to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame two years ago in Brooklyn and behind them, for 25 minutes, was a hundred foot high image of the Miracle Mile shot.

BM: Amazing. It was also up behind Kendrick Lamar when he introduced them, which I thought was really cool.

Kendrick Lamar, N.W.A. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Introduction, 2016

IDP: Seeing Kendrick up there, present the award to one of my images, that was a very special point in my career. I understand what you’re saying, some people don’t understand that it’s a weird period of time for intellectual property. People can and do hijack photos whenever possible, but you know theres so much that goes in to a photograph. Obviously there’s technical ability, but you also need to be lucky enough to have access and then to get the job done. It’s kind of a hidden part of the whole spectrum. I think these days there’s a little more attention coming back to an analog period of time that could have really easily been erased. It’s nice to see credits creeping back in through Instagram. To know who really shot the images and it not being so anonymous. It’s our life and our career, you know, it’s what we live for.

BM: Today with digital cameras it’s easy to bang off a thousand pictures without any thought or financial commitment. But shooting film back in the day, that wasn’t the case at all.

IDP: That’s what I was saying about the day in Venice with Eazy. I had only about six rolls of film with me, which was actually a lot for that period of time for that kind of shoot. I was covering everything pretty well but then Eazy appears on a skateboard! I didn’t know how taking those shots would fit in to the overall film supply for the day but I wish I would have been able to shoot way more of that moment.

BM: Before we wrap things up, I wanted to ask you about a potentially touchy subject. As I understand it, Universal Music has what amounts to a treasure trove of N.W.A photos that no one has ever seen, that you shot during their prime?

IDP: Yes that’s true.

BM: Can you explain why no one has seen these images?

IDP: Sure I’ll explain. I shot all those N.W.A and Eazy-E images as a freelance contractor for Priority Records. The agreement most photographers had at the time for record covers and magazine shoots was that the label would pay you a small fee and also cover the cost of your supplies. After the shoot, they would take the film for a while and they would use the images exclusively for six months to a year. Then they would send the negatives back to you.

BM: So what happenend in your case?

IDP: In my case, a year after I shot my last N.W.A images in 1991, I was no longer living in the country. Whenever I came back to L.A. I would go to the Priority offices and they would let me go to the photo cabinet and use the photos however I wanted. They were still an independent label so that’s just how they rolled. I didn’t really see a need to take the negatives home because they were still being used by Priority and I also was out of the country most of the time anyway. If I needed an image i would go to Priority to borrow a negative and bring it back. Or I would just make a print there, whatever worked.

N.W.A Record Store Autograph Signing Contact Sheet by @_Ithaka, 1989.

BM: So the negatives were safer at the Priority offices then at your home?

IDP: Exactly. That was the way I looked at it. I was living overseas and I didn’t have a physical home in LA. But the thing is, while I was out of the country, Priority was sold to Capitol Records. So the next time I go back there to make a print, it was like, guards up! I couldn’t even get past the front desk. I couldn’t even get in there.

BM: You explained to them that you were the N.W.A photographer?

IDP: Of course, they just ignored me. Then I had to go back to my life overseas. Eventually Capitol was acquired by Universal, so that’s who has them now. I do have access to some black and white images which is why most of the N.W.A images I work with today are black and white but the thing is that eighty percent of the N.W.A images I shot were actually colour. These are the images that are in the Universal vault that no one has seen.

BM: So what your saying is that we’ve seen only twenty percent of the hundreds of photos you shot of N.W.A and Eazy-E between 1988-91?

IDP: Possibly even less. There were times when I didn’t shoot any black and white at all, only colour.

BM: Have you asked Universal to just borrow the negatives and then return them?

IDP: I’ve contacted them several times with the best intentions, talking about collaborating on a book together. You know, culturally these images are really important to the hip-hop community. These are some of the founding fathers of controversial and influential art and hip-hop and most of these images have never even really been looked at before

BM: What does Universal say?

IDP: They don’t give an adequate response or they give me the run around. It’s really a shame because of the times, what’s going on, these images are I think becoming more important. There’s like a gap, an image gap, in the history of N.W.A which can actually be filled.

BM: Why do you think it is that they won’t let you access them?

IDP: I don’t know. I mean, I know it would be good for their catalogue to have those images out there. I know it would be good for the band. And it’s also good for me. So it looks like a win-win situation. You know, these were the images commissioned by Priority and Ruthless, so it’s like the real stuff. We need to get these out there in book form. My immediate goal is to release all those images in a book.

BM: Don’t the rights automatically fall to you in this case?

IDP: Yeah, the images and copyright belong to me absolutely. The second you snap an image without a contract the photographer owns the image.

BM: It’s too bad because this is also the 30th anniversary of the release of Straight Outta Compton and Eazy-Duz-It, so what a great year it would be to bring those images to the world. Lastly, are there any other artists out there, new or otherwise, that you find really interesting? That you’d love to shoot?

IDP: I’d love to shoot Kendrick. Can you hook that up?

BM: No sorry. How about we send him a tee?

IDP: Perfect.

Interview by Blazedmade founder, Daniel Cutler

https://itunes.apple.com/us/artist/ithaka/69363540

Interview by Blazedmade founder, Daniel Cutler

https://itunes.apple.com/us/artist/ithaka/69363540

https://store.cdbaby.com/artist/Ithaka2

https://www.instagram.com/_ithaka_/?hl=en

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm5225987/

https://thehundreds.com/blogs/content/ithaka-interview

https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ithaka

No comments:

Post a Comment